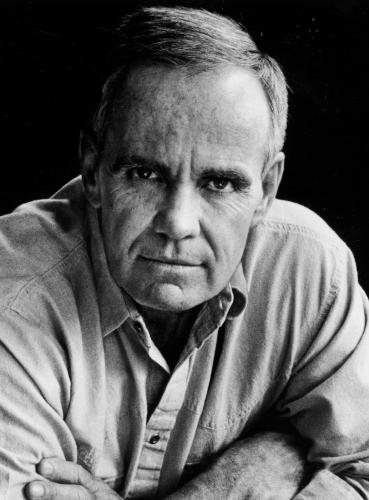

In “The Road,” a lean poetry captures many ruinous beauties-for instance, the way that ash, a “soft black talc,” blows through the abandoned streets “like squid ink uncoiling along a sea floor.” This third style has, in truth, always existed in McCarthy’s novels, though sometimes it appeared to lead a slightly fugitive life. The third style holds in beautiful balance the oracular and the ordinary.

One of the most moving scenes in “The Road” involves a father and son discovering an unopened can of Coke, as if in some parody of Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories, with the father having to explain to the son just what this fabled object once was. Meanwhile, the deflatus mode suddenly made both literary and ethical sense, since a world nearly stripped of people and objects would necessitate a language of primal simplicity, as if words had to learn all over again how to find their referents.

But the imagination had much less difficulty in “The Road,” where a similar rhetoric floats over the ashen landscape of an annihilating catastrophe. It might have been hard to credit, say, contemporary Knoxville as the ruined city that McCarthy describes in his earlier novel “ Suttree” (1979), a giant carcass that “lay smoking, the sad purlieus of the dead immured with the bones of friends and forebears . . . The afflatus mode was vindicated by the post-apocalyptic horrors of the material. McCarthy’s novel “ The Road” (2006) can be seen as both the fulfillment and the transformation of this profligately gifted stylist, because in it the two styles justified themselves and came together to make a third style, of punishing and limpid beauty. The words stagger around their meanings, intoxicated by the grandiloquence of their gesturing: “God’s own mudlark trudging cloaked and muttering the barren selvage of some nameless desolation where the cold sidereal sea breaks and seethes and the storms howl in from out of that black and heaving alcahest.” McCarthy’s deflatus mode is a rival rhetoric of mute exhaustion, as if all words, hungover from the intoxication, can hold on only to habit and familiar things: “He made himself a sandwich and spread some mustard over it and he poured a glass of milk.” “He put his toothbrush back in his shavingkit and got a towel out of his bag and went down to the bathroom and showered in one of the steel stalls and shaved and brushed his teeth and came back and put on a fresh shirt.”

McCarthy in afflatus mode is magnificent, vatic, wasteful, hammy. There have always been two dominant styles in Cormac McCarthy’s prose-roughly, afflatus and deflatus, with not enough breathable oxygen between them.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)